I've brought up the idea of peak oil on this blog a few times before. It's a topic that's starting to enter the mainstream's consciousness the way global warming was 10 years ago. I think it's going to loom larger and larger as oil production flattens and/or falls, and demand for oil keeps going up.

The Wall Street Journal this week pretty much said: Peak Oil, Not Just For Wackos Anymore. OK, so maybe they call it an "oil production plateau" and not peak oil, but the concepts of "energy shortages, high prices and bare-knuckled competition for fuel" are similar.

And so far I've talked a lot about renewable energy sources such as solar and wind, but they won't solve the problem of peak oil, at least not by themselves. That's because there are no realistic solar vehicles, and the idea of a wind-powered boat, or "sail" boat, is ridiculous. Oh wait...

Jokes aside, our country's transportation is 90% dependent on oil. So to avoid the Energy Crunch of peak oil, we're going to have to come up with another way to fuel our cars and trucks, and quickly. That is if we want to avoid paying massive prices for gas, having those price increases hit our middle and lower classes the hardest, entering a recession or possibly depression, having our gas money go into the hands of countries that hate us, and possibly tangling militarily with other large economies vying for oil around the world.

I'll take a look at three ways we can kick the oil habit: electric vehicles, hydrogen vehicles, and biofuels. I'll start today with electric vehicles which, in my mind, have suffered badly from poor PR and from some of the most unfortunate car designs ever to hit the road. This has cemented them in the average consumer's mind as the car of the be-turtlenecked tree-hugger with his head in the clouds, a car no real man would ever be caught dead in. What a tragic error!

I've said it before and I'll say it again. Change will have to make sense where it matters most:

in the pocketbook, and well in this case, the consumer's ego. So this Thanksgiving many many thanks go out to

Tesla Motors, whose new roadster (right) has changed everything. Finally a good-looking electric car which, oh by the way, completely dusts the Ferrari going from 0-60.

So maybe now we can leave behind those lame wheel-covered designs and make a nice electric car. But what about the pocketbook? Won't an electric car be too expensive because of the battery?

Let's do the math. New electric cars are piggybacking off the extraordinary amount of research that's been done on Lithium-Ion batteries for cell phones and laptops, and the idea is that one of these batteries for a car might add $1,200 to the price. That's a big hit... until you think about the money you save.

Here are some assumptions. Electric cars use about 0.215 kWh per mile. Cost of a kWh from the electric company (at least for me here in L.A.) is 10.5 cents. MPG of an internal combustion engine vehicle is 23 (U.S. fleet average). I used $3/gallon prices, as well as the new and improved $5/gallon we'll be paying soon (ok, that's just a guess for now), and I came up with the following annual costs of fueling your vehicle to go 12,000 miles:

At those rates, here is the money you'd save after five years of using an electric car versus the car you drive today, and that's including the battery:

I don't know about you, but I could use the extra $10 grand. And mass production of these vehicles would reduce our dependence on that dwindling supply of oil, helping us avoid the problems I mentioned above. And to top it off, you'll be pumping less pollution into the air, especially as more of the electrical grid is powered by renewables. How could a mass-produced electric vehicle fail? Detroit, Japan, and Germany - market opportunity beckons.

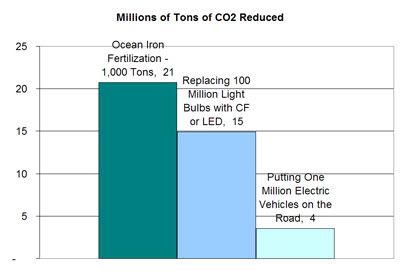

I wanted to revisit the Ocean Iron Fertilization idea I mentioned in my last blog post, to run the numbers and see if it's worth the controversy. I found out some interesting things.

I wanted to revisit the Ocean Iron Fertilization idea I mentioned in my last blog post, to run the numbers and see if it's worth the controversy. I found out some interesting things.